wrestling / Columns

The 8-Ball 05.31.12: The Top 8 Careers After 40

Welcome, ladies and gentlemen, to the 8-Ball. As always, I am your party host, Ryan Byers, and, I’m still hanging my head in shame after the feedback to last week’s column, which I think will forever be referred to as “Wooo-gate.” But, hey, that’s what happens when you have no time to write your column throughout the week and have to whip something up in 30 minutes.

However, let’s not dwell on that. Instead, let’s move along to a brand new column with a brand new set of eight entries.

Your new topic is after the banner . . .

Last week, I celebrated a bit of a milestone birthday. I won’t say exactly what it was, but the number ended in a “0.” For most of us, this sort of a birthday is a time for reflection, and, though some react more strongly than others, virtually all of us will have some degree of negative reaction to aging, even if we are on the whole happier with it than not.

Since I was thinking quite a bit about getting older this past week, I decided that today’s column would focus on the eight wrestlers who have had the best in-ring careers after reaching forty years of age. I’m not talking about the top eight wrestlers who continued wrestling after forty. I’m talking about the eight wrestlers who would have the best careers if we considered only what they did after hitting the big 4-0.

So, without further ado, here are wrestling’s eight best golden oldies.

Born on November 27, 1950, Gran Hamada made his professional wrestling debut at the age of 22 after training in the dojo of New Japan Pro Wrestling. From there, he was sent to wrestle in Mexico, particularly for the UWA promotion centered around Canek, where he was a perpetual star and a multi-time champion, including a run with the WWF Light Heavyweight Title. (Yes, that WWF.) In addition to that, he was also a popular lower-card wrestler in Japan’s shoot-style UWF, where he helped round out the promotion’s lower weight classes. Upon turning 40 in 1990, the man didn’t slow down and, if anything, kicked his career into high gear. He was still active in the Mexican UWA, where he exchanged championships with members of legendary families Los Villanos and Los Brazos. However, where his career really exploded was in his native Japan. Instead of trying to fit into traditional puroresu-style or the modern UWF-style, he took matters into his own hands and founded his own promotion, alternately called Universal Pro Wrestling and Federacion Universal De Lucha Libre, the purpose of which was to introduce a Mexican-style of pro wrestling to the Land of the Rising Sun. The young wrestlers that Hamada nurtured in F.U.L.L. went on to become major stars, some in WCW (Ultimo Dragon & Kaz Hayashi), some in the WWF (TAKA Michinoku), some in Michinoku Pro Wrestling (Great Sasuke, Dick Togo, Jinsei Shinzaki, & Super Delfin), and some in New Japan Pro Wrestling (Gedo & Jado). These men would travel throughout the country and even the world, spreading a brand new style developed in F.U.L.L called “lucharesu,” a hybrid of puroresu and lucha libre.

However, perhaps Hamada’s proudest accomplishment was his daughter, Ayako Hamada, who he trained for her professional wrestling debut in 1998. Though Ayako’s sister Xochitl was also trained by daddy and debuted as a wrestler in 1986, going on to become a heckuva performer in her own right, it is Ayako who has developed a reputation as one of the best female wrestlers of the last fifteen years, in large part due to the lessons learned from her father. In fact, in 2000, the same year that Gran Hamada turned 50, the daddy-daughter duo set foot into the ring as a tag team and captured the P-Mix Championship of ARSION, contested in a single-elimination tournament of mixed tag teams.

Start your own promotion, popularize a brand new style of wrestling, train a generation of awesome workers, and turn your daughter into an all-time great all after the age of 40? Yeah, that gets you on the list.

Most people who appear on this list appear on it because they started wrestling in their teens or 20’s and had particularly long careers. However, in the case of manager-turned-wrestler “Diamond” Dallas Page, he didn’t even have his first match until 1991, when he was already thirty-five years of age. Page was a lower-to-midcard wrestler for several years, and he didn’t even really start to ascend until 1996, when he returned from a several month absence caused in storyline by dropping a fall to the Bootyman – yes, the Bootyman – in a loser leaves town match.

When Page came back to the squared circle, WCW essentially strapped a rocket to his ass. He won the Battle Bowl tournament, a semi-regular competition in WCW. That year, the Battle Bowl winner was awarded a championship ring, and Page essentially defended the ring as though it were any other title, which gave him an opportunity to win numerous “championship” matches and engage in feuds across the midcard. He was winning far more than he was losing, and, when the New World Order invaded just a few months after his return, that put him in prime position to be one of the top WCW wrestlers defending the promotion’s home turf. Page was turned face in an angle that played off of his prior storyline connections with Outsiders Scott Hall and Kevin Nash. Though the one big knock against World Championship Wrestling during the late 1990’s is that they never created any stars of their own and instead relied solely on ready-made names from the WWF, the fact of the matter is that WCW really did take this angle and create, a legitimate, homegrown star with Page.

Dallas, after a few angles with Nash and Hall, turned his attention on “Macho Man” Randy Savage, having a wild feud with several brutal matches that truly put him over the top in the fans eyes and made him into a main eventer. From there, he had runs with both the United States and World Heavyweight Championships, including feuds with the likes of Raven, Chris Benoit, and Goldberg that were very entertaining both in and out of the ring. Cap that off with a super-hot tag team run as part of the Jersey Triad, and you’ve got the makings of an a-plus career for Page. Though the WWE-written history books often don’t portray him this way, he was consistently one of WCW’s top three babyfaces when that company – and professional wrestling as a whole – were at the height of their respective popularities. Though things started to go downhill for DDP once WCW lost ground to the WWF in the Monday Night War, the several years that he had on top in WCW when WCW was on top of the industry are more than enough to qualify him for this list.

Lucha libre star Satanico was born on October 26, 1949 and made his pro wrestling debut at the ripe old age of fourteen. (They do things a little bit differently in Mexico than they do here in the United States, if you couldn’t tell.) This means that Satanico would have turned 40 in the late 1980’s, which was really only the mid-point of his career. Satanico first gained substantial notoriety as one of the first major “trios” in lucha libre, pairing up with partners MS-1 and Pirata Morgan to form Los Infernales. It is fitting, then, that his post-40 success really began with a reformation of the Infernales in the early 1990s, as the group became the first ever CMLL World Trios Champions and dominated the division in its early years. Around the same time, Satanico also had a singles feud with popular wrestler El Dandy, which is notable for the fact that the men traded victories in two hair matches held within one year of each other, whereas a hair match would oftentimes be the blowoff of a feud. Perhaps most notable during this time period, though, is the fact that Satanico won the CMLL World Middleweight Title in 1994 at the age of 45 and held it for a mind-blowing 1,561 days, eventually losing it in 1999 at the age of 50. Needless to say, this is a record that will most likely not be broken at any point in the near future.

As the 1990s closed out, Satanico took on more of a mentor role in professional wrestling, as he formed a new version of Los Infernales with Rey Bucanero and Ultimo Guerrero. In part due to Satanico’s tutelage, Bucanero and Guerrero would develop greatly as wrestlers and be considered the best tag team in all of professional wrestling for a period of time in the early and mid-2000’s. When there was a storyline split between Bucanero, Guerrero, and Satanico, the old man landed on his feet and immediately became the mentor to another team of up-and-comers who would subsequently become world-renowned performers, namely Averno and Mephisto.

However, Satanico wasn’t just mentoring young wrestlers in front of audiences and in CMLL’s storylines. In the early 2000’s, he became the head trainer at CMLL’s training camp and produced an impressive crop of students. In addition to the aforementioned Averno, Satanico has also turned out the likes of Dragon Rojo, Jr., El Texano, Jr., and La Sombra. Satanico’s legacy continues to grow to this day, in part because he continues to train rookies and in part because, believe it or not, he is still not fully retired from the ring, despite turning 63 this year.

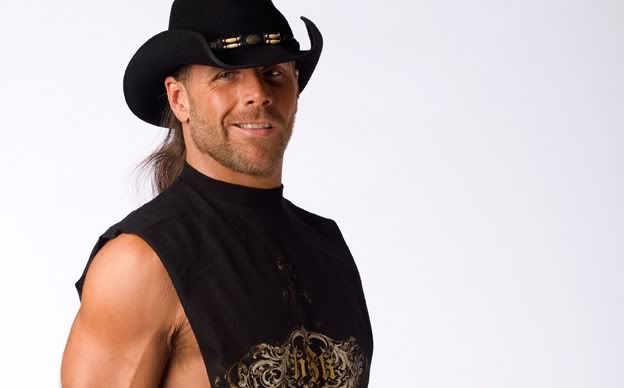

Just about everybody reading this column is going to be familiar with Shawn Michaels, so I don’t have to give a lot of his backstory and I probably don’t even have to spend much time justifying his inclusion on the list. I would bet that, if anything, the people who react to Shawn Michaels being here will argue that he should have been placed higher than number five. So, why is Michaels in fifth and not first? The fact of the matter is that, even though he did some spectacular things after reaching the age of 40, he didn’t stick around in wrestling for too much longer after hitting that magic number. In fact, Michaels would’ve had that birthday in the year 2005, and he retired in 2010, so we are really only talking about less than five years as an in-ring performer that can be considered to justify HBK’s inclusion on this list.

They were an absolutely AWESOME five years, though, and, in that time; Shawn Michaels accomplished more and had more great matches than most wrestlers will have in fifty years. Just weeks after turning 40, Shawn clashed with another legendary performer, Hulk Hogan, for the first time in a significant program. Their match is quite memorable, as was Michaels’ subsequent feud, which saw him war with Vince McMahon en route to reforming D-Generation X with longtime running buddy Triple H. The next year, Michaels really had to cover for his pal, as a planned HHH vs. John Cena main event for Wrestlemania XXIII was ruined by an injury to Trips, leaving Michaels to step up into the championship program and save the show. A few weeks later, Michaels and Cena would meet again and have one of the most memorable matches in the history of Monday Night Raw as HBK would carry Cena, who is not known as a good in-ring performer, to a surprisingly decent hour long match in the United Kingdom.

And, of course, the last two highlights of Michaels’ in-ring career were his feud with Chris Jericho and his trilogy of epic Wrestlemania matches against Ric Flair, the Undertaker, and the Undertaker one more time at Manias XXIV-XXVI. The former permitted Michaels to have one of the most critically acclaimed feuds of the past decade, while the latter produced two matches that will never be forgotten and the moment in pro wrestling history that has probably caused more grown men to cry than any other.

It may not have been a long run, but Shawn Michaels’ career after forty is the best five year period that a wrestler could hope for.

Everybody knew this one was coming. Announcers and fans first started referring to Terry Funk as “middle-aged and crazy” when he was in his forties. Care to wager a guess as to when the Funker entered that age bracket? NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR. The year prior, Funk had retired from professional wrestling the first time, engaging in an epic, supposedly-career-ending tour of Japan. However, the break lasted only slightly more than a year, with Terry getting back into the ring for All Japan Pro Wrestling, the company that hosted his retirement ceremony, in November 1984. Terry and his brother, Dory Funk, Jr., were not damaged at all by the faux retirement and remained a main event level tag team in Japan throughout the remainder of the decade. It was also during this period that Terry Funk had his first run as part of the World Wrestling Federation, primarily engaging in a feud with the Junkyard Dog and also having a fondly remembered house show loop of matches against Hulk Hogan that culminated with the two men wrestling on Saturday Night’s Main Event. After spending more time in Japan, Funk returned to the United States on a near full-time basis to engage in a rivalry with the man who many would consider to be Hogan’s closest rival for the title of best wrestler in the world, “The Nature Boy” Ric Flair. The Flair-Funk “I Quit” match is still remembered as one of the best of Flair’s career, which is saying something given Naitch’s resume.

The 1980s were great for Terry Funk, but the scary thing is that he barely slowed down at all in the 1990s. There, the Funkmaster discovered hardcore wrestling, competing in brutal, bloody brawls for both ECW and Japanese promotions such as FMW, W*ING, and IWA Japan. In addition to wrestling atop explosives in the Orient, Funk had two insane ECDub barbed wire matches, one with his brother Dory against the Public Enemy and one singles war with the maniacal Sabu. However, the man from the Double Cross Ranch also proved that he could still go in straight matches, winning the ECW Championship in the relatively clean main event of the company’s first pay per view in 1997 and, in 1994, helping put the same promotion on the map with an hour-long three way match against Sabu and Shane Douglas that is still referred to as “The Night the Line Was Crossed.”

Somewhat surprisingly, Funk managed to parlay his cult fame in ECW and FMW into another run at the big time, as the World Wrestling Federation re-signed him in the late 1990s and he was portrayed as one of the key stars of the documentary film Beyond the Mat during that period. This also gave him another turn in WCW in 2000, including a brief United States Championship run at the age of 56. Though he has not worked full-time with a pro wrestling company since that WCW stint, the Funker has remained active as a freelancer, still delighting crowds every time he steps into an arena.

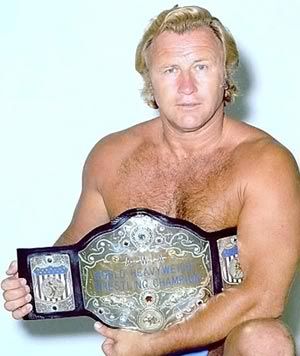

Nick Bockwinkel started wrestling at the fairly typical age of twenty-one. However, for many years, he was either confined to relatively small circuits or was in the big leagues as a tag team wrestler, most notably with Ray “Crippler” Stevens. The second generation wrestler from St. Paul, Minnesota did not become a world heavyweight champion in a major promotion until the year that he turned 40, as he upended Verne Gagne’s apple cart (to use a phrase Verne himself probably would have) to earn the top title of the American Wrestling Association.

Bockwinkel would go on to become a four-time AWA World Heavyweight Champion, with his first reign lasting almost five years and with his list of challengers reading like an international “Who’s Who” of professional wrestling. As champion, Bockwinkel would put the title on the line against a diverse group of competitors that included the Brit Billy Robinson, Japan’s Jumbo Tsuruta, French Canadian Mad Dog Vachon, and the Austrian star Otto Wanz. Many competitors would have difficulty with such a wide-ranging group of opponents, but Bockwinkel was the consummate professional and was able to put on acceptable matches with just about any performer who stood across the ring from him, regardless of their style or level of talent. In addition to being a world class performer in between the ropes, it was also during this period that Bockwinkel developed a reputation as one of the best interviews in professional wrestling. He was not bombastic or over the top like many of his brethren but instead presented a calm, cerebral style of promo that on occasion even managed to overshadow the legendary Bobby “The Brain” Heenan, who was paired with Bockwinkel as a manager for much of his championship run.

Towards the end of his time with the AWA Championship (which, in fact, was also largely the end of his time in professional wrestling), Bockwinkel helped to usher in a new generation of stars, as he engaged in feuds with the likes of Curt Hennig and a pre-WWF Hulk Hogan. Bocnkwinkel was briefly an on-screen commissioner for WCW after retiring, but, by and large, he has stayed out of the limelight for the past several years. He doesn’t really need the limelight, though. He had more than enough of it during his active in-ring career.

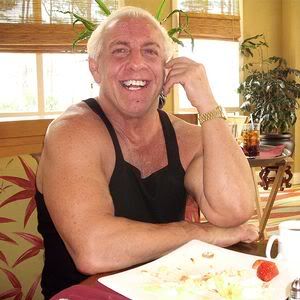

There are probably many people who are surprised that Ric Flair didn’t run away with number one on this list. After all, Flair hit 40 in early 1989, after which he had several of his legendary matches with Ricky “The Dragon” Steamboat, the aforementioned feud with Terry Funk, two WWF Championship reigns, a return to WCW to do battle with Vader, a rivalry with the nWo, a run as the “co-owner” of the WWF, a hand in molding Randy Orton and Batista’s careers via Evolution, a surprisingly good Intercontinental Title run late in his career (which helped earn him 411mania Wrestler of the Year), and one of the most memorable retirement matches and ceremonies in the entire history of professional wrestling . . . and this is the SHORT list of his accomplishments.

However, for everything that Flair accomplished after 40 and for as big of a Flair fan as I was for the majority of his run, I still couldn’t bring myself to put him at number one. Part of that has to do with the career of the man who is actually at number one. Another part of it, though, has to do with the last three years of Ric Flair’s career. Flair, after retiring and voluntarily leaving WWE in order to take lucrative deals doing outside autograph signings and conventions, has become more of a wrestler to pity than a wrestler to revere. Stories of severe financial trouble have cropped up, Flair has allegedly stiffed reputable companies like Ring of Honor and Highspots, alimony payments are mounting, his physical appearance is deteriorating, and, more and more, Ric Flair starts to look more like a guy who continues to be involved in wrestling because he can’t afford to stop working than a guy who continues to be involved in wrestling because he has a burning passion for it.

So, despite all of the memories (which I am told I should leave alone), the current, sad state of Ric Flair plays a big part in him not topping this list.

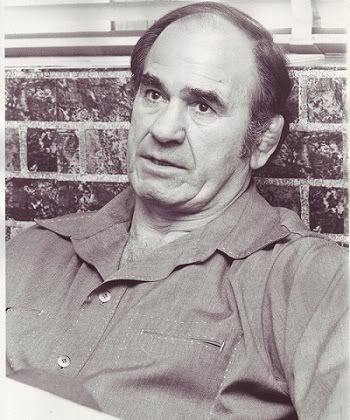

In addition to being a hell of an in-ring technician, Lou Thesz’s greatest claim to fame is that he was professional wrestling’s first “undisputed” World Heavyweight Champion after several decades in which the top prize in the game was severely fragmented and claimed by a number of competitors, some of whom were nowhere near credible enough to be considered a top champion. After debuting in 1932 and wrestling for slightly more than fifteen years, Thesz started a run in which he began to wrestle these supposed champions one-by-one until he had accumulated virtually every “splinter” world championship that had a shred of credibility. This culminated in 1956, when he had obtained virtually all of these belts and unified them into the NWA World Heavyweight Title before defending it for several years, leading to his conclusively being referred to as the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world. What else happened in 1956? That’s right, in 1956, Lou Thesz turned forty.

However, accomplishing this goal and hitting the big 4-0 did not result in Thesz slowing down as a professional wrestler. It is true that he dropped his undisputed championship later in 1956, but he also regained it that same year. In 1957, Thesz began touring Japan for the first time, and he immediately became one of that country’s first top foreign box office attractions, feuding with puroresu founder Rikidozan and, in the process, legitimizing Japanese professional wrestling and helping to grow it into one of the most popular forms of entertainment in the country.

Thesz was also not done with wrestling in the United States. His career picked up steam again in the early 1960s, at which time he began a rivalry with then-NWA World Heavyweight Champion “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers. In 1963, at the age of 47, Thesz defeated Rogers to win the title in a match that would directly result in the formation of the World Wrestling Federation due a schism between promoters and who they wanted to bill as champion. He would hold the NWA version of the championship for three more years. After dropping it, Thesz continued to travel the world, remaining a popular attraction in Japan and the United States and even adding Mexico to the list of countries that he conquered, becoming an early heavyweight champion for the ultra-popular UWA lucha libre promotion in the late 1970’s. As with many wrestlers on this list, Thesz also gets a bit of extra credit for becoming a trainer, as he mentored young Masahiro Chono, who is now known as one of the biggest box office attractions in the history of Japanese wrestling. Thesz passed his patented finishing hold, the STF, along to Chono, and the move has also been adopted by another modern world champion who you might have heard a thing or two about.

Thesz also authored Hooker, one of the definitive pro wrestling autobiographies, a few years before his 2002 death. The book provides a needed window into a bygone era of wrestling, an era that Mr. Thesz dominated, both before and after he turned 40.

More Trending Stories

- Jade Cargill and Bianca Belair Comment On The Importance of Representation, Being Role Models For Girls

- Backstage Notes on This Week’s WWE NXT Talent Releases, When WWE Decided to Cut Drew Gulak

- WWE Releases NXT Talents Valentina Feroz, Boa, Trey Bearhill, More

- Michael Cole Reportedly Stepping Back From Backstage WWE Role, Will Remain As A Talent